Some Notes on Block Ciphers

Some Notes on the Cryptanalysis of Block Ciphers

The following are some notes on the cryptanalysis of various block ciphers - most from the self-study course by Bruce Schneier.

Rotationless RC5

Algorithm

Here, we ignore the key expansion step instead letting S be the expanded subkeys. The encryption goes as follows:

void RC5_ENCRYPT_NO_ROTATION(WORD *pt, WORD *ct)

{

WORD i, A = pt[0] + S[0], B = pt[1] + S[1];

for (i = 1; i <= r; i++)

{

A = (A ^ B) + S[2*i];

B = (B ^ A) + S[2*i + 1];

}

ct[0] = A; ct[1] = B;

}

Note that for bitwise XOR and addition, the least significant bits of the result only dependon the least significant bits of the operands. More explicitly, given two words A and B of bit length w, we have for any \(k \le w\) that

Since these are the only operations used by the encryption algorithm, this proprety extends to the entire algorithm. Therefore, to recover the subkeys, we can simply bruteforce over all possibilities starting from the least significant bit. Some pseudocode for this algorithm is given below:

Given: list of equations of the form enc(pt_i) = ct_i

curr_bit = 1

curr_subkey_guess = [all 1 bit possibilities for subkeys]

while curr_bit <= w:

filter out any subkey guesses that don't conform to the given equations

extend all guesses by 1 bit

curr_bit += 1

Here is a Python implementation of this attack on a reduced 4 round version of this cipher; however, the general attack strategy remains the same for any number of rounds.

DES

Here, we briefly describe the DES algorithm, again ignoring the key expansion steps (below is pseudocode in Python-like syntax):

subkeys = expand_key(key)

L, R = apply_bit_permutation(plaintext, IP)

def feistel(x, subkey):

x = expand(x) # Expands x from 32 bits to 48 bits

x ^= subkey # Key mixing

x = substitute(x) # Apply S-boxes

x = apply_bit_permutation(x, P)

return x

for i in range(ROUNDS): # Typically 16

L, R = R, L ^ feistel(R, subkeys[i])

ct = apply_bit_permutation( R || L, IP_INV)

In order to assist with learning, an implementation of DES was made that allowed for the usage of normal Python integers as well as symbolic bit-vectors from the z3 library. This allows us to represent the state of the entire cipher symbolically - for example, we can check that decryption is indeed the inverse of encryption:

from des import DES

import z3

z3.set_param('parallel.enable', True)

z3.set_option(verbose=20)

key = z3.BitVec("k", 64)

pt = z3.BitVec("p", 64)

cipher = DES(key = key, rounds = 16)

s = z3.Solver()

s.add(pt != cipher.decrypt(cipher.encrypt(pt)))

print(s.check())

(combined-solver "using solver 1")

(simplifier :num-exprs 1 :num-asts 1015947 :time 9.03 :before-memory 135.27 :after-memory 266.42)

simplifier

(goal

false)

unsat

DES with no S-Boxes

Note that in encrypytion, the only non-linear operation comes from the S-box. Therefore, removing it makes the entire encryption process affine. Let

\[\begin{align*} \text{DES}_{\text{NO_S_BOX}}: \mathbb{Z}_2^{56} \to (\mathbb{Z}_2^{64}\to \mathbb{Z}_2^{64}) \\ k \mapsto E_k: (p \mapsto c)\end{align*}\]be our new encryption function. For any given key \(k \in \mathbb{Z}_2^{56}\)

we have that the corresponding map \(E_k\) is affine. We can therefore construct a linear map from \(E_k\)

\(L(x) = E_k(x) \oplus E_k(0)\).

Note that given the encryptions of \(0\) and all \(e_j\) we can construct the matrix of this linear map: \(M=\begin{bmatrix} \vert & \vert & \cdots & \vert & \vert \\ f(\hat{e_1}) & f(\hat{e_2}) & \cdots & f(\hat{e_{63}}) & f(\hat{e_{64}}) \\ \vert & \vert & \cdots & \vert & \vert \\ \end{bmatrix}\), where \([\{\hat{e_j}\}_{0<j\le64}] = I_{64}\) is the identity matrix.

It remains an exercise of algebra to construct the decryption map:

\[D_k(x) = M^{-1}(x \oplus E_k(0))\]Below is some Sage code that implements this. Note that DES uses 8 different S-boxes that each produce a 4 bit output from a 6 bit input. For this weakened version of DES, I made each of these S-boxes simply return the middle 4 bits of the 6 bit input (i.e. \(\mathtt{x} \mapsto \mathtt{(x \& 011110_2)>>1}\) )

With this, we can see that our constructed decryption map correctly decrypts 10000 randomly chosen plaintexts.

TODO: Prove that this actually works with Z3.

from des import DES

from functools import reduce

import random

from tqdm import tqdm

from sage.all import GF, matrix, vector

IDENTITY_S_BOX = {i: [(j & 0b011110) >> 1 for j in range(64)]

for i in range(8)}

def _popcnt(X): return bin(X).count('1')

def _add_parity_bit(X): return (X << 1) | (1 if _popcnt(X) % 2 == 0 else 0)

def gen_des_key(key_bits): return reduce(lambda x, y: x | y, [_add_parity_bit(

(key_bits & (0b1111111 << (7*i))) >> (7*i)) << (8*i) for i in range(8)])

key_bits = random.randint(0, 2**56)

des_key = gen_des_key(key_bits)

cipher = DES(key=des_key, rounds=16, Sboxes=IDENTITY_S_BOX)

L = lambda p: cipher.encrypt(p) ^ cipher.encrypt(0)

# Construct a matrix representing L

_to_bit_vec = lambda X: [(X & (1<<i)) >> i for i in range(64)]

_from_bit_vec = lambda v: reduce(lambda x,y: x|y, [int(v[i]) << i for i in range(64)])

M = matrix(GF(2), [ _to_bit_vec(L(1<<i)) for i in range(64)]).T

# It is now trivial to invert this map

M_inv = M.inverse()

decrypt = lambda ct: _from_bit_vec(M_inv * vector(GF(2), _to_bit_vec(ct ^ cipher.encrypt(0))))

for _ in tqdm(range(10000)):

pt = random.randint(0, 2**64)

ct = cipher.encrypt(pt)

assert decrypt(ct) == pt

Attacks on Reduced Round DES

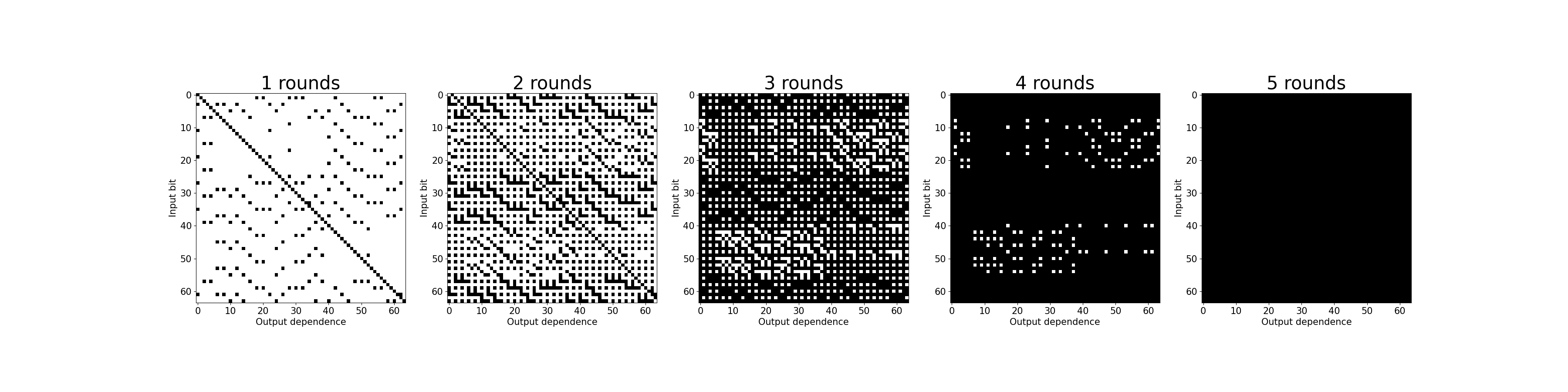

In attacking a reduced number of rounds of DES, note that if we use a smaller number of rounds than the recommended 16 then we may not get the necessary amount of diffusion. We can empirically test this as follows:

- choose a random key \(K\) and a random plaintext \(P\)

- encrypt the plaintext \(C = E_K(P)\)

- encrypt another plaintext with a 1-bit difference \(C' = E_K(P \oplus \Delta_X)\) and observe the difference in ciphertext \(\Delta_Y = C \oplus C' = E_K(P) \oplus E_K( P \oplus \Delta_X)\)

By observing 5000 of such random pairs, we can observe that most input/output dependence is lost after 4 rounds, with all dependence being lost after 5 rounds:

We can also view this by the following - by encoding the logical conditions of the encryption and solving with a SAT solver for varying number of rounds, thr average time it takes to recover the cipher’s key is given as follows (here we use CryptoMiniSat to recover a key given 3 plaintext/ciphertext pairs):

| Rounds | Time |

|---|---|

| 1 | 3.28s |

| 2 | 6.35s |

| 3 | 11.35s |

| 4 | 39.12s |

| 5 | >3600s |

From these times, we can see that there is a large jump in complexity from between 4 rounds and 5 rounds.

Attempting to Break 5 Rounds

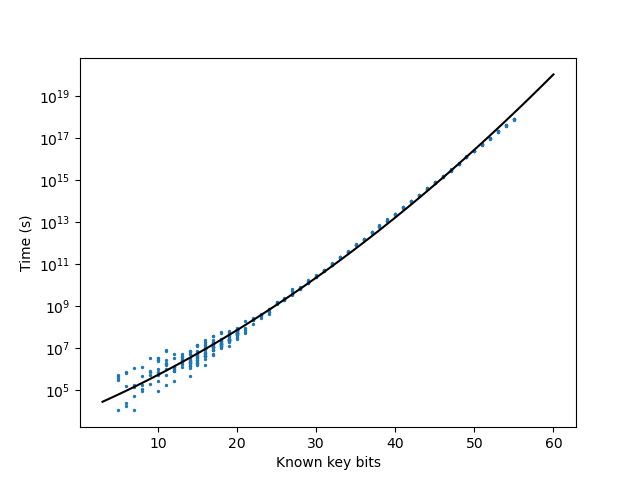

Following the approach given in this paper, instead of directly solving for the key we instead fix \(k\) of the key and then solve for the remaining bits with a SAT solver. This will either give us the rest of the bits of the key, or the SAT solver will fail to find a solution - indicating that our partial guess was wrong. Iterating over all \(2^k\) possibilities of what bits our partial guess could be, we will eventually guess the correct key.

To estimate the time that this approach would take, for varying \(k\) we generate a random DES key and fix \(k\) of the bits. We then encode the conditons of encryption into CNF form and attempt to solve for the remaining bits with CryptoMiniSat. Below is a plot of how long such an approach would take for varying values of \(k\)

From extrapolating the best fit line on the above plot, this kind of attack would take \(\approx 10^5 s\) on a single core.

It is difficult to make a one-to-one comparison between such an approach and a brute force one for several reasons - a major one being that a SAT solver’s heuristics will prune down the key’s search space in a manner that a brute force approach would not be able. Additionally, we are making several assumptions in order to simplify the analysis (e.g. the choice of the bits we guess has no effect on the time taken by the SAT solver, searching for a solution takes the same amount of time as not finding any solutions).

However, even with generous assumptions, a SAT-solver based approach like the one described is orders of magnitude faster than a naive brute force approach. With a quick shell script, we can benchmark approximately how long a single DES encryption takes.

#!/bin/bash

tmp_file=$(mktemp)

dd if=/dev/urandom bs=1024 count=500000 2>/dev/null > $tmp_file

time_start=$(date +%s.%N)

openssl enc -des-ecb -e -K 133457799BBCDFF1 -provider legacy -provider default -in $tmp_file > /dev/null

time_end=$(date +%s.%N)

echo "$time_end - $time_start" | bc

rm "$tmp_file"

With this, we can see that encrypting \(8 \cdot 10^6\) blocks takes approximately \(6.6 s\) or approximately \(8.2 \cdot 10^{-7} s\) per encryption. At this speed, a full brute force of all \(2^{56}\) DES keys would take 1800 years; our SAT-solver based attack only takes an equivalent of \(\approx 2^{37}\) DES encryptions.